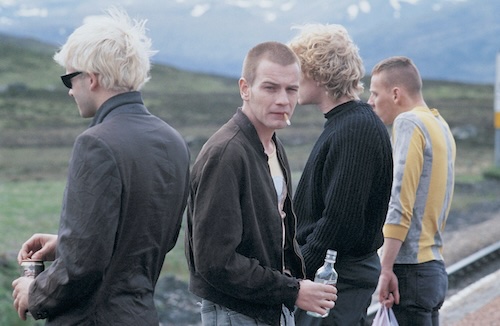

A thunderous blast of Iggy Pop's 'Lust for Life' kicks off one of the finest British movies of the 1990s, Trainspotting, which plays on May 28th and concludes our Danny Boyle season. "Choose life, choose a job..." implores Ewan McGregor's Mark Renton as he and his pals tear through the streets of Edinburgh pursued by store security guards.

The framing of the imagery and the spotting of the music, accentuated by a piercing, fourth-wall freeze frame as Renton laughs directly into the camera, sums up the dichotomies inherent in this Danny Boyle classic. The pumping music and editing is a salute to the energy of youth and the camaraderie of friendship. Yet, of course, Renton and his buddies are heroin junkies, which lends a darkly unsettling irony to the proceedings, and indeed the whole film.

Can we trust that what Renton says has any sincerity or integrity whatsoever? Maybe his words are just a breathless, flippant expression of what it takes to score the next hit, be it heroin, stealing, or some other form of transgressive behaviour.

Those familiar with Trainspotting will know that Renton's opening monologue is recontextualised with a greater sense of insight at the end of the movie. The character's progression through the seamy side of Edinburgh society ultimately leaves him cleansed and with a greater sense of clarity.

In between those two poles lies the meat of the film itself, and it's still a strong brew, even after all these years. Trainspotting was adapted to Oscar-winning effect by screenwriter John Hodge (later to become a Danny Boyle regular) from Irvine Welsh's vernacular novel and, at the time, was described as the 'A Clockwork Orange of the 90s'. It's not hard to see why.

Like Stanley Kubrick's film, Trainspotting is a less-than-flattering depiction of youthful vice. Populated with pub violence, scatological humour and graphic, close-up drug use, not to mention infanticide and more c-bombs than a Malcolm Tucker convention, Trainspotting is uncompromising for how it immerses the viewer in a wrong-side-of-the-tracks lifestyle.

Also like Kubrick's film, Trainspotting paints vividly and boldly with its use of music. A Clockwork Orange began with Wendy Carlos' eerie synth interpretation of Henry Purcell's 'Funeral of Queen Mary'. Trainspotting begins with 'Lust for Life' and punk rocker Iggy Pop's growly intonations do more than open the film.

Renton and his friends verbally express their appreciation of Iggy Pop's music throughout the film, showing us that, as with Malcolm McDowell's Alex DeLarge and Beethoven in A Clockwork Orange, music plays an active part in shaping one's identity.

The music of Trainspotting is a reflection of both character and cultural norms. The film was released in 1996, post-Generation X and mid-Britpop, placing it at a fascinating cultural crossroads that allows Boyle to mix and match a host of musical idioms from rawness to ecstatic jubilation.

GQ quotes Boyle as saying: “We decided early on that we weren’t going to score the film in a traditional way, so you look at the masters. You look at the way that Scorsese – particularly in Mean Streets – uses his music. One of the ways we can actually identify the period is to move from Iggy Pop through to dance music – [when] Renton moves to London and goes to a rave – right up to Pulp, Blur, Sleeper and Elastica.

"The film’s timespan is impossible because Renton doesn’t age and they don’t cut their hair, but you feel you’ve moved through a period of time on a sensual rather than documentary level."

Sensual is exactly the word. Iggy Pop's propulsive punk style shares space with contemporary Lou Reed's ironically expressive 'A Perfect Day' whose lyrics, vividly describing a drug trip, accompany Renton's horrific overdose scene as he apparently sinks into his squatter's carpet. The dreamily ambient synths of Brian Eno's 'Deep Blue Day' are used to offset the movie's grossest scene in which Renton disappears into the 'worst toilet in Scotland' to retrieve an anal suppository.

Sleeper's ecstatic cover of Blondie's 'Atomic' leads us from a club scene into the first encounter between Renton and Diane (Kelly McDonald), the resolution to which is typically provocative and shocking. Boyle shows loyalty to the group Leftfield, whose music opened the director's 1994 film debut Shallow Grave, by incorporating their track 'A Final Hit'.

Blur's atmospheric 'Sing' is perhaps the film's most overt concession to mid-1990s trends. Although the song was released in 1991, its placement on the Trainspotting soundtrack came at the onset of the Blur/Oasis Britpop rivalry, reiterating the film's pop culture relevance and status to a contemporary youth audience.

The film was also quick to capitalise on Pulp's jaunty 'Mile End', released in 1995, in which Jarvis Cocker reminisced, appropriately enough, about his foul living arrangements in the 1990s. It fits beautifully with Trainspotting's aesthetic: there's a serious point to be made about standards, but the delivery is heightened, playful and surreal.

Trainspotting is therefore able to use music as both a sociological tool and a potent form of tonal expression. The soundtrack's release carried as much currency as the film itself, akin to the sensationalism that would have once accompanied Elvis Presley's joint film-album releases back in the 1950s and 1960s.

Two Trainspotting albums were released, the first in February 1996 to coincide with the film's release and the second in October 1997. The former went three times platinum in the UK, a clear sign of its piercing ability to communicate with disaffected, disgruntled youth, not to mention its slick ability to coast off the back of Britpop and post-punk trends.

Boyle has always painted vividly with music. One thinks of his collaborations with John Murphy on the likes of 28 Days Later (2002) and Sunshine (2007), which variously act as contrasts between suspenseful electronica ('In the House in a Heartbeat') and soaring, elegiac beauty ('Adagio in D-Minor). Even so, the use of music in Trainspotting is special.

It's not just a technical tool, the kind that has been used by filmmakers since time immemorial. It's an additional layer of dialogue that speaks to both inner and outer states of being, not to mention it also reflects both a dramatic narrative and the contextual circumstances in the film was released.

Boyle goes hard at the end of the film, entrusting the propulsion and significance of the last 10 minutes to Underworld's thunderous 'Born Slippy. NUXX'. On the one level, it's a slice of electronic club nirvana whose lyrics, describing an alcoholic's experiences with the bottle, dovetail with the film's narrative about going clean.

And yet by becoming the leading diegetic sound tool in the film's closing stages, the music encapsulates Boyle's ability to use music as its own form of dialogue. Barring Renton's emotive closing voiceover, we don't need overt exposition: as with the rest of the film, the music does most of the storytelling for us.

It's pumped intravenously into our veins and we understand exactly where we are: positioned in a specific time and place, having gone through the dark and emerged into the light with Renton as our guide. Boyle later described the track as the "heartbeat" of the film, describing its "euphoric highs following intense lows".

It's among many lacerating soundtrack cues that make us choose life. Do the same and click the link below to book your £5 tickets for Trainspotting at Cineworld.

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)