In anticipation of Star Wars: The Rise of Skywalker's release this December, we're counting down all the Star Wars movies in chronological order of release.

We're starting at the beginning with George Lucas's seminal introduction to the saga: Episode IV - A New Hope.

What's the story of Star Wars: Episode IV - A New Hope?

A long time ago, in a galaxy far, far away, an intergalactic war is raging between the Rebel Alliance and the evil forces of the Empire.

The rebels have attained plans of the Empire's top-secret new weapon known as the Death Star, which is capable of obliterating entire planets. Princess Leia (Carrie Fisher) is intercepted by the forces of Darth Vader (David Prowse, voiced by James Earl Jones) – but not before she's able to hand the plans to droid R2-D2 (Kenny Baker).

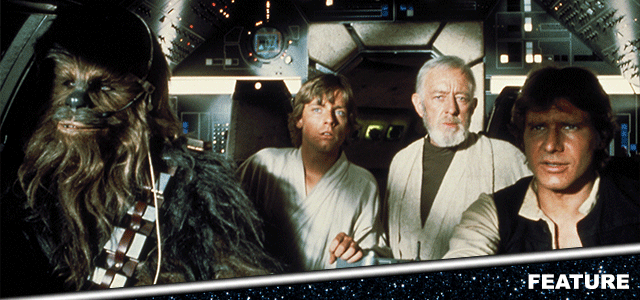

Along with prissy fellow droid C-3PO (Anthony Daniels), R2-D2 is stranded on the desert planet of Tatooine where they're picked up by moisture farmer Luke Skywalker (Mark Hamill).

The seeds of an epic adventure and a sweeping saga are sown when Luke teams with Ob-Wan Kenobi (Alec Guinness), a Jedi master who's wise in the ways of the Force, and cocky space cowboy Han Solo (Harrison Ford). Together they seek to rescue Leia from Vader's clutches, and help the rebels destroy the Death Star once and for all.

What's the background of A New Hope?

When the first Star Wars movie arrived in 1977, it was at the tail end of one of Hollywood's most radical and creative periods.

Throughout the late 1960s and most of the 1970s, American film-making had been consumed with counter-culture voices, independently-minded directors and assorted artists drawing inspiration from the hippy movement and the collapse of American foreign policy in Vietnam. This period came to be known retrospectively as 'New Hollywood'.

Consequently, Hollywood films around this time were among the most creatively liberated and politically angry ever produced. The likes of Dennis Hopper's Easy Rider (1969), Robert Altman's M.A.S.H. (1970) and Alan Pakula's Klute (1971) showed a willingness to engage with America's wider sense of disillusionment. In 1976, Martin Scorsese's Taxi Driver painted an unforgettably bleak, hellish picture of New York that seethed with repressed anger and distorted morality.

It was a very different state of affairs from the cinema of the 1950s where the studio system (20th Century Fox; Paramount et al) still held sway over Tinseltown, a period populated by expansive, and expensive, historical romances and Biblical epics like The Ten Commandments.

This was also a period where star-driven vehicles dominated theatre marquees – yet at the same time, a revolution in the form of youth cinema was emerging, embodied by the brooding, relatively unknown likes of James Dean.

All of a sudden, young audiences were being given a mainstream voice in cinema, paving the way for the generational shifts of the 1960s and 1970s where verisimilitude, non-professional actors and a disregard for narrative clarity gave voice to the complexities of a changing American society.

While indie, rebellious cinema was thriving in the first half of the seventies, at the same time a group of creatively knowledgeable and cinema-literate individuals, aspiring film-makers known derisively as the 'movie brats', were coming to prominence.

The group was exemplified by directors like Steven Spielberg, George Lucas, Francis Ford Coppola and Brian De Palma, a team whose collective output was as generation-defining as any before. While Spielberg would go on to birth the summer blockbuster with 1975's Jaws, Coppola would deliver The Godfather (1972), a stately masterpiece of the crime genre that would revive the career of Marlon Brando and cement itself as one of the greatest films ever made.

Brian De Palma gained a reputation as a purveyor of lurid, melodramatic and bloody horror-thrillers, his first major success being 1976 Stephen King adaptation Carrie. As his career progressed, he developed an affinity of assimilating the films of Alfred Hitchcock via the likes of Dressed to Kill (1980).

Interestingly given where his career ended up, Lucas started off as one of the more experimental and low-key of the group. His arrestingly minimalist sci-fi drama THX 1138, released in 1971, was one of the defining sci-fi films of its period, drawing inspiration from George Orwell's 1984 in its depiction of a future where all sense of humanity and identity is suppressed.

Later, in 1973, Lucas would deliver a nostalgic ode to his own youth with American Graffiti, a coming-of-age story that ambles between various 1950s high school students on the final evening of summer vacation. Soaring off the back of a jukebox soundtrack, it helped launch the careers of many of its players including Ron Howard (later to become a celebrated director in his own right), Richard Dreyfus and a certain Harrison Ford.

The movie distilled the nostalgic hopes and dreams of Lucas's generation, the post-World War II 'Baby Boomers' whose relative affluence and affinity for traditional, narrative-driven Hollywood cinema and TV serials created an emotionally powerful connection with audiences.

His reputation established, Lucas then embarked on a celebration of the fantasy and adventure stories with which he'd grown up – Star Wars...

How did A New Hope get made?

It's worth noting that Star Wars only became known as Star Wars: Episode IV – A New Hope in a retrospective sense. At the time of its release Lucas, not to mention distributor 20th Century Fox, had no way of knowing this unassuming movie would birth eight additional films in the context of one of the biggest franchises of all time.

But let's back up a bit. Following the indie pluck of THX 1138 and American Graffiti, Lucas set his sights even higher with an ambitiously staged space opera, one that would fly in the face of Hollywood trends and embrace the old-fashioned storytelling conventions that, at the time, had somewhat fallen out of favour.

Each character in A New Hope, be they the mentor/wizard (Obi-Wan), the sidekick (C-3PO), the hero (Luke) or the Princess (Leia) owed themselves to the kind of deep-seated archetypes that have long resonated through popular fairy tale storytelling. In the process, A New Hope would owe more to the audience-pleasing magic of The Wizard of Oz than the bleakness of something like Klute, each character occupying a clearly identifiable role in a relatable story of good versus evil.

In short, the first Star Wars movie would be a universe rendered in popcorn-pleasing black and white, rather than the morally troubling shades of grey with which mid-seventies audiences had become accustomed.

In fact, Lucas had first conceived of the idea of Star Wars in 1971, and the commercial failure of THX 1138 was said to have directly informed A New Hope's optimistic tone. In Lucas's own words: "I wanted to make a Flash Gordon movie, with all the trimmings, but I couldn't obtain the rights to the characters."

Unable to secure the rights, Lucas set out to make his own Flash Gordon-riffing serial. He began writing the movie in earnest in January 1973, writing "eight hours a day, five days a week". Various drafts ensued between that point and the final iteration in March 1976, by which time the movie had started filming.

He derived inspiration from author Edgar Rice Burroughs' (of Tarzan fame) John Carter of Mars stories, plus an Edwin Arnold 1905 story called 'Gulliver of Mars'. This was cited by Lucas as the earliest example he could discover of "the hero battling space creatures" while "having adventures on another planet".

Along the way the story incorporated additional mythological elements, including the Sith and the Death Star. Various elements changed during production itself, including Luke's surname change from Starkiller to Skywalker, and Han Solo's transformation from a green-skinned alien into a recognisable human figure. (Obi-Wan's death was also added later when Lucas couldn't work him into the film's final act.)

"It's the flotsam and jetsam from the period when I was 12 years old," Lucas told New York Times when the movie was originally released. "All the books and films and comics that I liked when I was a child. The plot is simple –good against evil – and the film is designed to be all the fun things and fantasy things I remember. The word for this movie is fun."

Pitching the movie to studios was tricky – science-fiction wasn't especially popular at the time, with United Artists turning Lucas down, and Universal Pictures shying away on the basis that the concept was "a little strange". Ironically, and more than a little amusingly, Disney also showed little interest in distribution.

Lucas and producer Gary Kurtz eventually managed to get 20th Century Fox head Alan Ladd Jr. to secure a deal in June 1973, the movie mogul eventually stumping up $150,000 for Lucas to write and direct the movie. Thanks to American Graffiti's positive reception, Lucas was also able to negotiate with Ladd to secure merchandising and sequel rights, although he stressed that Ladd "invested in me, not the movie".

Unbeknownst to the studio at the time, Lucas had just secured one of the most lucrative and brilliant deals in the history of motion pictures. The flowering of Star Wars as a major franchise would fall entirely under his financial jurisdiction, eventually making Lucas one of the most powerful and wealthy figures in Hollywood.

Mark Hamill was urged to audition for Luke Skywalker at the behest of friend Robert Englund (later immortalised as dream-invading serial killer Freddy Krueger). Having secured the role, he received $1,000 a week during shooting, plus a quarter of a per cent of the film's profits; he later netted $1 million for The Empire Strikes Back.

Several actors were in line for the role of Han Solo including Kurt Russell and Christopher Walken, before Harrison Ford clinched it. Al Pacino also turned the part down, later saying the decision was the one he most regretted in his career.

Carrie Fisher was semi-established through her role in 1975 Hal Ashby comedy Shampoo, before her casting as Leia shot her to stardom. Lucas raved of her performance: "She was extremely smart; a talented actress, writer and comedienne with a very colourful personality that everyone loved. In Star Wars she was our great and powerful princess – feisty, wise and full of hope in a role that was more difficult than most people might think."

Alec Guinness was famed as one of the leading lights of British cinema, having delighted in Ealing comedy classics like The Ladykillers, and moved with his Oscar-winning performance in The Bridge on the River Kwai. Although he dismissed Star Wars as "fairy tale rubbish", adding, "some of the dialogue is excruciating", Hamill, Ford and Fisher cited his presence on the set as an inspiration.

The sheer scale and ambition of A New Hope resulted in Lucas forming his own visual effects company, Industrial Light and Magic, which would exert a powerful influence in its own right on future Hollywood blockbusters.

He worked with production designer John Barry to create a "used future" look that was tactile, lived-in and dirty – in fact, the production assistants spent five months planning out the various props and set designs. This was occurring in London even before 20th Century Fox had signed on the dotted line – famous examples include the eggcup-laden visualisation of the Death Star surface during the final rebel assault. Other examples include scrap metal sourced from airplane parts used in the Millennium Falcon set.

Principal photography officially began on 22nd March 1976 in Tunisia, standing in for Tatooine. (Death Valley in the USA was also used to depict sand-blasted desert landscapes.) Interestingly, that particular planet was written as a jungle location, but owing to Lucas's squeamishness about filming in such an environment, it was changed to an arid setting.

Following tricky conditions on the set including a rare Tunisian rain storm, production moved to Elstree Studios where the vast interior sets were constructed, plus an additional one at neighbouring Shepperton Studios to house the rebel hangar.

Lucas's reportedly remote demeanour on the set, plus his cast and crew's lack of faith in the overall concept, led to a somewhat strained atmosphere. Ford is famously quoted as saying of the script, "You can type this s**t George, but you can't say it".

With the budget rising and the movie falling behind schedule, Alan Ladd Jr. was compelled to shield Lucas from the involvement of nervous executives. (The movie was originally budgeted at $8 million before it rose to just shy of $10 million.)

Gary Kurtz said: "We proceeded to pick a production plan and do a more final budget with a British art department and look for locations in North Africa, and kind of pulled together some things. Then, it was obvious that eight million wasn't going to do it – they had approved eight million."

Post-production was no less stressful – Industrial Light and Magic didn't have a pre-existing template to work off, and their pioneering visual effects shots were regularly shot down by the exacting Lucas. To inspire the crew during the creation of the aerial battles, he showed them dogfighting scenes from classic World War II movies, but it didn't make the overall process any easier.

Much material was cut out of the movie following a reportedly disastrous first edit – much of Luke Skywalker's introductory material hit the editing room floor. Sound designer Ben Burtt had to create nothing less than a brand new organic language to do justice to Lucas's vision – the lightsabers, for example, were a combination of the hum of idling interlock motors in aged movie projectors and interference caused by a television set on a shieldless microphone. (Further upset was caused when Lucas swapped out Darth Vader actor David Prowse's Somerset tones for the booming cadence of James Earl Jones.)

Lucas screened at early cut of the movie in 1977 to an audience of assembled executives and film-makers, including Steven Spielberg, Brian De Palma (who had helped trim down Lucas's iconic opening crawl text), John Milius (later to direct Conan the Barbarian) and Alan Ladd Jr. According to Spielberg, he was the only person who loved the movie, although he thought the absence of finished effects in the edit dampened enthusiasm among the others.

Further delays to the movie saw the budget swell even further to $11 million. Second unit photography covered exterior shots in Guatemala (acting as the exterior of the rebel base), while Lucas initially planned to rework the Han Solo/Jabba the Hutt confrontation with stop-motion creature effects. However, as time and money grew tight, he was compelled to drop the sequence before later reinstating it in the 1997 Special Edition re-release.

- Star Wars: The Rise of Skywalker – 6 possible theories as to the meaning of its title

- 8 things we already know about Star Wars: The Rise of Skywalker

- Everything you need to know about the Emperor's return in Star Wars: The Rise of Skywalker

How did John Williams compose the score for A New Hope?

Composer John Williams was hired for Star Wars on the recommendation of Lucas's friend Spielberg, with whom Williams had collaborated to Oscar-winning effect on Jaws.

Williams was already established as a composer and pianist of repute, having won an Oscar for the 1967 adaptation of the Fiddler on the Roof. His work on Star Wars, however (replacing an earlier Lucas notion to use pieces from Holst's 'The Planets') would catapult him in the upper echelons of greatest-ever composers, film or otherwise.

Embracing Lucas's unashamedly earnest vision, Williams deployed the full force of the London Symphony Orchestra, building his score around recognisable themes aligned to certain characters and situations. (This approach is known as the 'leitmotif', credited to 19th century German composer Wagner.)

From the heraldic brass of the opening title sequence (nothing less than a statement of intent that knocks the audience back in their seat), to the yearning, melancholy strings of the Force theme (unforgettably used in the binary sunset scene), Williams's tapestry was the boldest Hollywood blockbuster score for some time.

Although many of Williams's contemporaries were enjoying success in symphonic film scoring at the time (his friend Jerry Goldsmith won an Oscar for 1976 horror The Omen), the early-to-mid seventies had seen a trend towards favouring pop and rock music. A classic example would be Martin Scorsese's Mean Streets, forgoing the need for an orchestral score in favour of hit staples like The Rolling Stones' 'Gimme Shelter'.

Around this time, pop musicians were themselves moving into soundtrack composing – the late Leonard Cohen composed the music for Robert Altman's McCabe and Mrs Miller in 1971.

Williams, however, singlehandedly ushered in a popular resurgence in the golden age Hollywood soundtrack, unashamedly playing on an audience's emotions in thrilling fashion. The score was brilliantly tailored to Lucas's desire to throw back to space opera serials and high adventure, cementing Williams's mastery of the medium.

What was the legacy of Star Wars: Episode IV - A New Hope?

Upon the release of Star Wars in May 1977, Steven Spielberg declared that George Lucas had "put the butter back into popcorn". Against the odds, the film-maker took the world by storm with his nostalgic and old-fashioned vision, the movie eventually amassing $775 million globally to become the biggest of all time (until Spielberg's E.T. the Extra Terrestrial toppled it in 1982).

Critical acclaim greeted the film: Roger Ebert spoke for everyone when describing it as an "out-of-body experience". The movie added artistic prestige to its popcorn credentials when it grabbed six Oscars, including Best Original Score for John Williams, Best Visual Effects and Best Sound. Such success helped secure the film's position as one of the greatest and most influential science-fiction movies ever made.

The movie spawned a merchandising frenzy and a host of imitators that span to this day. All of the fantasy film-making present throughout the 1980s, from Flash Gordon to Willow (produced by Lucas) owes itself to the popularity of Star Wars, archetypal characters and good vs evil scenarios very much back in vogue.

In recent years, critics have retrospectively cited the arrival of Star Wars (along with the earlier Jaws) as marking the end of the politicised, risk-taking 'New Hollywood' movement. Experimental cinema was seen to fall by the wayside as popcorn blockbusters surged back into life, mass audiences now pivotal to release strategy.

A New Hope led to an expansion of the saga storyline with sequels The Empire Strikes Back and Return of the Jedi (1983). Lucas would later revisit his original trilogy and introduce it to a brand new generation with his remastered special edits in 1997, incorporating improved effects sequences.

And the legacy of the series later spilled over into the 1990s and 2000s with Lucas's prequel trilogy, plus the Disney-distributed new saga that began with 2015's The Force Awakens, and assorted spin-offs including 2016's Rogue One: A Star Wars Story.

So what was the secret to the film's success? In short, Lucas reached out to those audiences both his age and older who had grown up admiring the sheer old-fashioned scale and ambition of rich Technicolour Hollywood epics like the aforementioned Ten Commandments. At the same time, he would also go on to inspire children growing up at the time, who were yet to receive their first exposure to such screen-filling wonderments.

Star Wars was a true event that united people from across the generational divide as they sought rousing, emotional escape from a troubled world. Here was a universe everyone could believe in, breath in and take solace in. Little wonder Lucas's creation has endured to this day – we now find ourselves desiring the clear-sighted morality and human principles of Star Wars more than ever.

What was the next entry in the Star Wars saga?

Star Wars Episode V: The Empire Strikes Back was the next entry in the franchise, released in 1980. Stay tuned to the Cineworld blog over the coming weeks for your breakdown of the movie.

When is Star Wars: The Rise of Skywalker released?

Star Wars: The Rise of Skywalker is released on 17th December. Tweet us your favourite Star Wars moments @Cineworld.

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)